Last week we talked about how “Cloud-first” isn’t good strategy.

The corporate world is rife with examples of bad strategy. Defined as strategy that does not contain:

A clear goal

An insightful diagnosis

Meaningful guiding principles

A coherent action plan

Examples of bad strategy (which are a mix of my own and some that Rumelt gives in Good Strategy Bad Strategy) are:

A bank: Our fundamental strategy is one of customer-centric intermediation. (In other words, their strategy was to be a bank.)

A graphics arts company: Revenues were to grow at 20 percent per year and the profit margin was to be 20 percent or higher. (But what was the strategy to achieve this…?)

A professional services firm: Our strategy is to focus on customer-centric business problem solving across two industry groups. (Which included all industries in the market.)

A technology team: Our strategy is to deliver our technology architecture roadmap. (What what was on the roadmap and what challenges was it meant to solve for the company?)

I could go on. But this article isn’t about what bad strategy looks like, as I think most of my readers are pretty good at spotting it.

But what do we do as a leader in an organisation when the strategy handed to us by the exec team or board or our VP/GM is “bad strategy”?

“Bad strategy” is different from “strategic failure”. Strategic failure is where a company decides to take a set of actions that results in significant loss or business failure. Bad strategy doesn’t always lead to business failure, but it doesn’t give us any tools to be successful. Most bad strategy is little different from having no strategy at all.

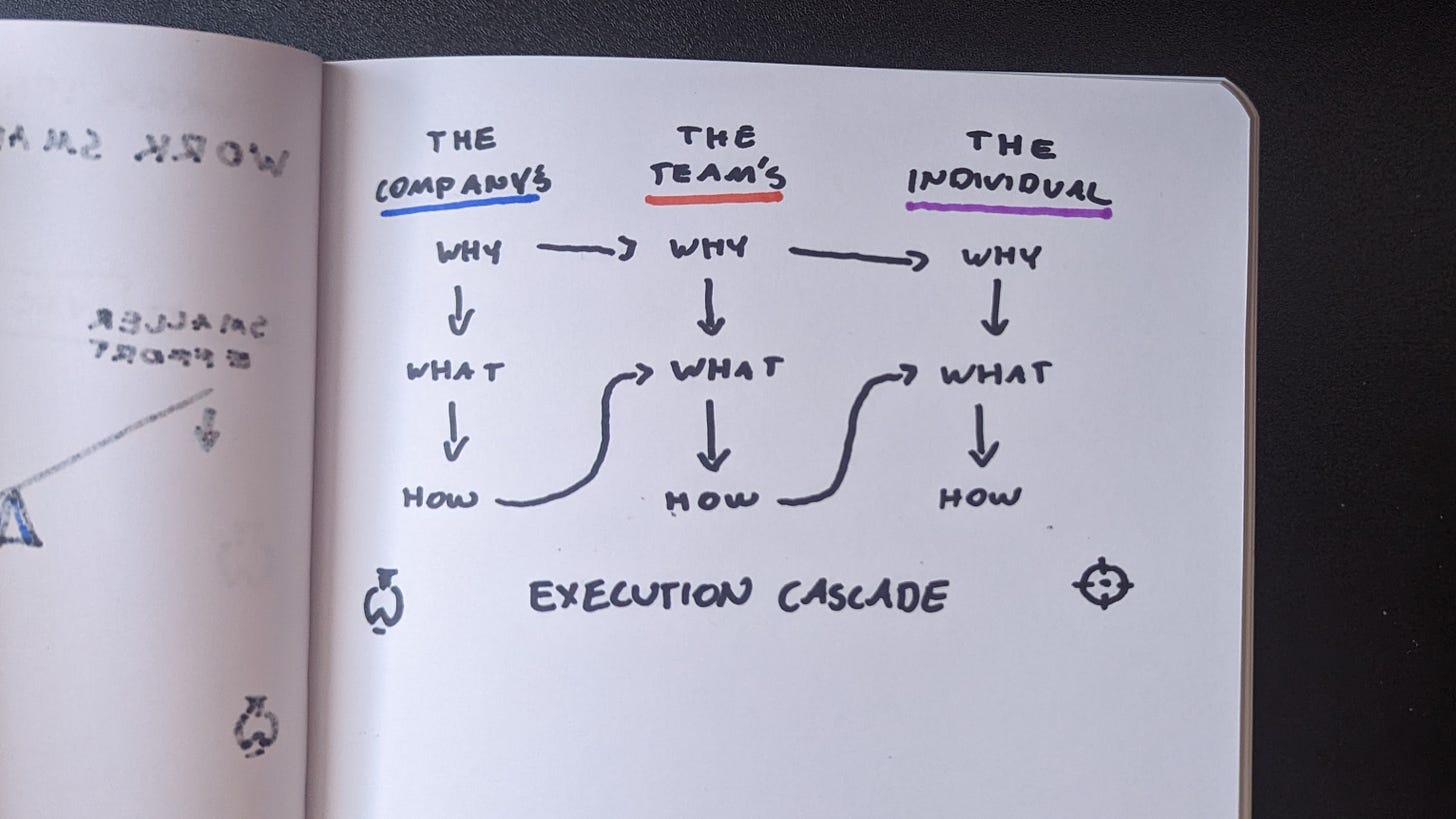

Thankfully however, strategy has to happen at all levels of the organisation. Even when an exec produces good strategy, it is usually described at the highest-level of the company’s concerns. A good strategy sets the context for the next layer of the business to determine how they will strategically achieve the coherent action plan set out at the top level. This cascade continues down all the way to the individual contributor level.

If you aren’t being given good strategy, you can still cascade the decision-making to make good strategy out of bad.

1. Find out what outcomes the company actually needs from your team (the diagnosis).

You may not be responsible for the entire value chain of the company, but your team will be delivering something valuable to the organisation. As a finance manager, you will be delivering accurate reporting, fiscal controls and insights into opportunities for improving financial outcomes. As a technology manager, you will be improving employee efficiency and experience with technology, securing technological assets, and keeping the lights on digitally speaking.

If the corporate strategy doesn’t discuss these functions, or doesn’t give clear guidance about how they fall into the coherent action plan, you can find out by consulting with your boss and other teams who rely on your team’s work.

2. Define a clear goal for the next strategic period (be this 6 weeks, 5 years, or anything in between).

The role your team plays in the corporation will give you a starting point for figuring out your goal. However, you may need further consultation to narrow this down to a clear overarching goal. This is part of the diagnosis that Rumelt describes in Good Strategy Bad Strategy. Identify what is the main challenge facing your organisation that falls within your team’s remit.

For example, for a technology team of a newly established subsidiary of a mining company, they had a huge laundry list of activities they needed to undertake. They were borrowing most of their parent company’s technology but had some specific requirements they needed to implement. There was a lot to get set up, an ERP transformation to deal with and not to mention lots of what they called “business as usual” activity such as responding to help desk queries and onboarding and offboarding employees.

Bad strategy would ask the IT manager to come up with a “catch all” statement describing all the work on that laundry list. Something like “update and secure the new technology architecture while supporting business as usual activities for employees”. Good strategy would have figured out what the most important value was for the IT team to deliver. For example, was the imperative cybersecurity? Meaning the team could delay upgrades to technology until their Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) tool was stood up. Or was the cyber risk low and the important goal was supporting more efficient financial reporting while sweating existing cyber controls?

3. Define your guiding principles.

Once you understand the most important thing for your team to achieve in your strategic planning period, figure out the guiding principles that will keep you on track toward it. A great example of what a guiding principle is comes from Apple’s transformation of their product lines when Steve Jobs returned to the helm. They set the guiding principle of reducing overwhelm of choice for their customers. That’s Jobs cut back the multiple product lines for just one in each category.

For example, the IT team I mentioned above had a choice of guiding principle. One option was to show investment across the full range of their scope (projects, security, service desk, architecture, etc.) by running multiple projects concurrently. Alternatively they could have chosen to accelerate results on one or two aspects of their role to show they were getting things done. Either was a valid option but would have resulted in different actions around how they allocated team members to work.

4. Determine your coherent actions.

Once you have diagnosed the main challenge your team needs to solve and set some guiding principles, the next step is to determine coherent actions to solve the challenge within the guiding principles.

Following our example of the overwhelmed IT team, they might have taken a strategic decision to close out projects more rapidly by working on fewer at once. And let’s say they worked out with the executive team that the ERP transformation was the most critical. This would have given the cyber team clear context to decide to delay their SEIM and email filtering implementations so that they could support with security requirements and integration for the ERP. And so on for the whole team.

Strategy is in your hands

Corporate strategy is often gatekept as if it is a magical skill that only a few ex-Wall Street brokers or white-haired consultants can work in. This leaves enterprises worse off because strategic acumen isn’t developed at all levels of the organisation. Even if the business is lucky to have actual good strategy written at that level (which is no guarantee), it will go no where if the rest of the business isn’t equipped to create the next level of strategy and execute on it.

If you’re interested to develop your strategic acumen, here are some resources I would recommend:

Good Strategy Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt (Amazon)

Roger Martin’s Medium blog (author of Playing to Win)

The strategy mini-series on the Work Upgraded podcast (starting at episode 11)

Go forth and make good strategy!